Imagine lying in a hospital unable to communicate in any way. You can hear, but you can’t move even the smallest muscle or make any sound.

Now imagine hearing doctors say your spouse is being “completely unreasonable” by refusing to donate your organs. You’re brain dead, you hear. Other patients need your organs. Her story was shared in part one and two of a video.

Jennifer Hamann owes her life to her completely unreasonable husband. Jenny had been diagnosed with epilepsy at 25. Medication prescribed for an unrelated illness turned out to be contraindicated for epilepsy, and it triggered her first grand mal seizures. Twice she was resuscitated, and she was left comatose.

Doctors were eager to harvest her organs, but Jenny was not brain dead. After three weeks she woke up. Over the next year she fully recovered. Afterward she became a nurse, inspired during the coma by some of the nurses who cared for her. “I was the recipient of good nursing care and not so good,” she said. “I wanted to be one of the good ones.”

To the not-so-good ones, “I wasn’t a person,” she said. “I was a body they were forced to take care of.” She heard a nurse call for help to “turn this thing,” and a doctor called her a “young, healthy specimen.”

Jenny’s experience is not unique. The sanctity of human life is on a collision course with the medical community’s willingness—even eagerness—to declare a patient brain dead and harvest his or her organs. In the US, organ donation led to 28,000 transplants in 2013, about 79 patients per day. But another 18 patients died each day “due to a shortage of donated organs.”[1] Clearly demand far exceeds supply.

As transplant expertise advances, the demand for organs grows. Some countries now use an opt-out system; unless a person specifically registers objection to being a donor, permission is assumed. In a study published September 2014, researchers looked at organ donation rates in 48 countries from 2000 to 2012, specifically studying kidneys and livers. Twenty-three countries used opt-in systems, including the United States, and 25 used opt-out. Researchers expected opt-out to produce higher donation rates, and their hypothesis proved true.[2]

These results are not surprising, given that opt-out makes organ donation the default. If a person wants to be an organ donor, no action is needed. On the other hand, if people avoid thoughts of death and delay opting out or simply never consider the question, the decision is made for them. If one does nothing, whether by ignorance, delay or choice, he or she is automatically a donor.

The default may carry additional authority if perceived as public policy or a social good. Organizations such as Recycle Yourself promote the latter. The Recycle Yourself website offers t-shirts and other “goodies” as well as Scalpel Pal, a “fun and interactive way” to learn about organ donation by playing “cool games” with friends on Facebook.

Even with opt-out consent, however, supply lags behind demand. Spain has the world’s highest rate of organ donation, but that was not always true. Despite using opt-out for a decade, Spain did not see a significant rise in donations until it introduced a transplant coordination network, placing procurement teams in hospitals and promoting organ donation among the public. Such hospital-based teams—the “Spanish Model”—are now common. Certified Organ Procurement Organizations are active in all 50 US states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. Their function is two-fold: “increasing the number of registered donors” and “coordinating the donation process when actual donors become available.”[3]

Interestingly, donation rates in France and Brazil fell under an opt-out system, an outcome attributed partly to mistrust of the medical community. The researchers also considered mistrust a factor in the United Kingdom’s decision to stay with opt-in consent. While the UK “reveres” its National Health Service (NHS), the system’s “shortcomings and failures” and financial realities are clear. Said Bruce Keogh, medical director of NHS England, “Medicine has become much more advanced, has become more complex and more effective, but importantly, it has also become more expensive.” Britain is “gripped in the quadruple pincer of increasing demand, escalating costs, a set of rising expectations, all in a constrained financial environment.”[4] That pincer is also inevitable as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—Obamacare—works itself out in the United States.

Given the cost of care and rehabilitation for brain-injured patients and the lucrative business of organ transplantation, the public is wise to be wary of the brain-death diagnosis, says Angela Clemente, a forensic analyst who consults for congressional investigations. Organ donation carries a connotation of generosity. Donations regularly make feel-good headlines, especially if the victim-donor is young. According to Clemente, an organ procurement team often knows the patient will be declared brain dead before the family knows.

When families are numb with grief and shock, the idea that their loved one may somehow live on through donation may offer comfort. Procurement teams are well aware of families’ vulnerability. They also are aware of families’ ignorance about brain death.

In August 1968, an ad hoc committee of Harvard Medical School published a report to redefine brain death, or irreversible coma. Death had long been defined by cessation of cardio-respiratory function, but medical advances made it possible to maintain those functions artificially. The committee itself signaled the controversy its definition would create in terms of patient care, family concerns, finite resources and transplants:

Improvements in resuscitative and supportive measures have led to increased efforts to save those who are desperately injured. Sometimes these efforts have only partial success so that the result is an individual whose heart continues to beat but whose brain is irreversibly damaged. The burden is great on patients who suffer permanent loss of intellect, on their families, on the hospitals, and on those in need of hospital beds already occupied by these comatose patients. Obsolete criteria for the definition of death can lead to controversy in obtaining organs for transplantation.[5]

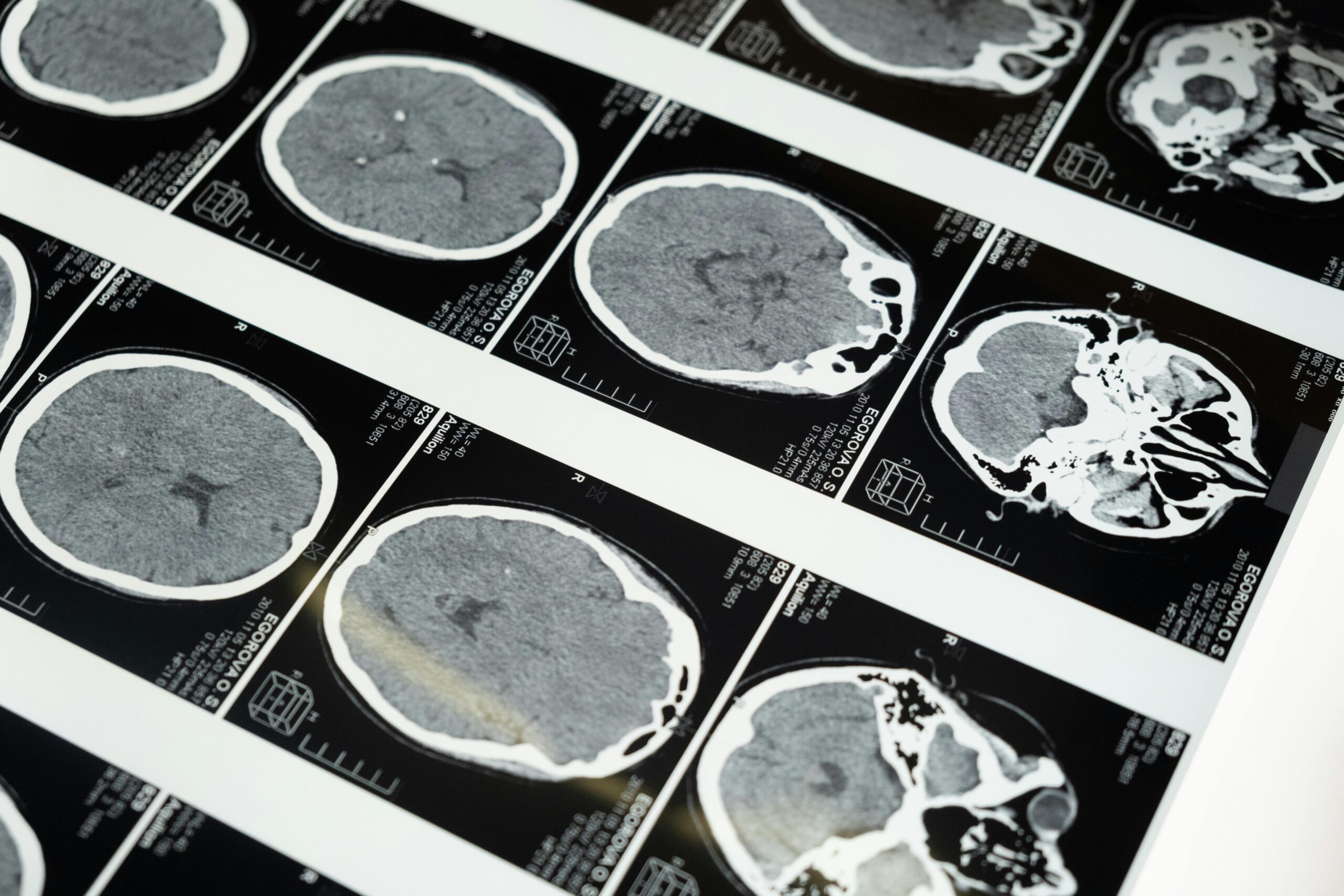

The diagnosis remains highly subjective. Any physician can determine brain death in most US states, but laws differ by state and even by institution. Some require the physician to have specialized expertise; others don’t.[6]

Theresa Dampf, a registered nurse whose patients are transplant recipients or potential recipients, recalled in-service seminars where instructors said patients have to be “100 percent brain dead.” She asked for clarification, noting that patients with as much as 50 percent brain function had been declared brain dead. Clarification was not forthcoming.

“Death occurs when life is absent,” said Paul Byrne, MD, who practiced 55 years and is president of the Life Guardian Foundation. “Life is gone with the destruction of three major systems: circulatory, respiratory and brain.” A physician may observe the absence of brain function, he noted, but function may not be gone. A damaged brain is slow to respond and slow to heal.

Diagnoses other than brain death may or may not be more accurate. For example, neurosurgeons first described persistent vegetative state in 1972, meaning patients have autonomic function controlled by the brain stem, such as heartbeat and respiration, but not higher functions such as thought and reason. Life Issues Institute takes exception to the language on its face—people are not vegetables—but in any case a study by London’s Royal Hospital for Neurodisability found the diagnosis to be wrong in 43 percent of cases.[7]

Another diagnosis, minimally conscious state (MCS), was described in 2002. MCS patients sometimes recover, even after years.

The diagnoses are fluid. A patient who appears to have only autonomic function may continue thus until the state is considered persistent but also could reach MCS. An MCS patient may retreat to only autonomic function. The timeframe for diagnosis depends on the cause of injury, whether oxygen deprivation or trauma. In the former, an autonomic-only state is considered permanent after three months; in the latter, 12 months is needed.[8]

Yet families often face pressure for organ donation within days of injury. If the patient is not a registered donor, Clemente noted, procurement teams may talk with family members separately to see if they disagree about donation. If so, the hospital’s ethics committee can step in and make the decision. The team may wait until a grieving family member is alone to push for donation.

Also, said Dampf, a family’s consent may not be informed consent. One common misconception is that the patient draws a last breath, the heart stops beating and the family is given time to say goodbye. In reality, organs are useless for transplantation after only four or five minutes without blood flow. For organs to be viable, the patient must be breathing and the heart must be pumping. The harvest can’t wait for death as the public perceives death.

Families may have few options, Dampf said, because once doctors declare a patient brain dead, insurance companies can refuse to pay for treatment after a specified period. Yet stories abound of “brain dead” patients who later recovered to varying degrees.

Caution on the side of life is the humane course. “When you are dealing with patients who seem not to be aware, you must treat them as if they are,” said Jenny Hamann. “You can’t know.”

Watch Facing Life Head-On episodes Surprising Realities of Brain Death and Organ Donation Part 1 and Part 2.

[1] “Organ donation: is an opt-in or opt-out system better?” Medical News Today, Sept. 24, 2014.

[2] Lee Shepherd, Ronan E. O’Carroll and Eamonn Ferguson, “An international comparison of deceased and living organ donation/transplant rates in opt-in and opt-out systems: a panel study.” BMC Medicine 2014, 12:131

[3] US Department of Health and Human Services organ donor resource materials. Accessed Sept. 8, 2015.

[4] Stephen Castle, “Britain’s National Health Service, Creaking but Revered, Looms Over National Elections.” New York Times, April 25, 2015.

[5] “A Definition of Irreversible Coma, Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death.” JAMA. 1968;205(6):337-340.

[6] University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, American Academy of Neurology Guidelines for Brain Death Determination. Accessed Sept. 8, 2015.

[7] Keith Andrews, Lesley Murphy, Ros Munday, Clare Littlewood, “Misdiagnosis of the vegetative state: retrospective study in a rehabilitation unit.” British Medical Journal, 1996 Jul 6; 313(7048): 13–16

[8] Joseph J. Fins, “Brain Injury: The Vegetative and Minimally Conscious States,” in From Birth to Death and Bench to Clinic: The Hastings Center Bioethics Briefing Book for Journalists, Policymakers, and Campaigns, ed. Mary Crowley (Garrison, NY: The Hastings Center, 2008), 15-20.

I live in Portland, Oregon. Do you know if there is a generic Opt Out form for organ transplant. I bookmarked a web site of a pro-life doctor who was an advocate for opting out, but it is no longer on my computer or I can’t find it. I believe he had forms on his web site Any help you can give me would be greatly appreciated We’re leaving on vacation in a few days and I want to have the forms signed and notarized before we leave. Thank you very much

Oregon

Pacific Northwest Transplant Bank

http://pntb.org/contact-us

This is a link for your state that is posted on our website here: https://lifeissues.org/resources/revoking-organ-donation-consent/

I hope this helps. God Bless!